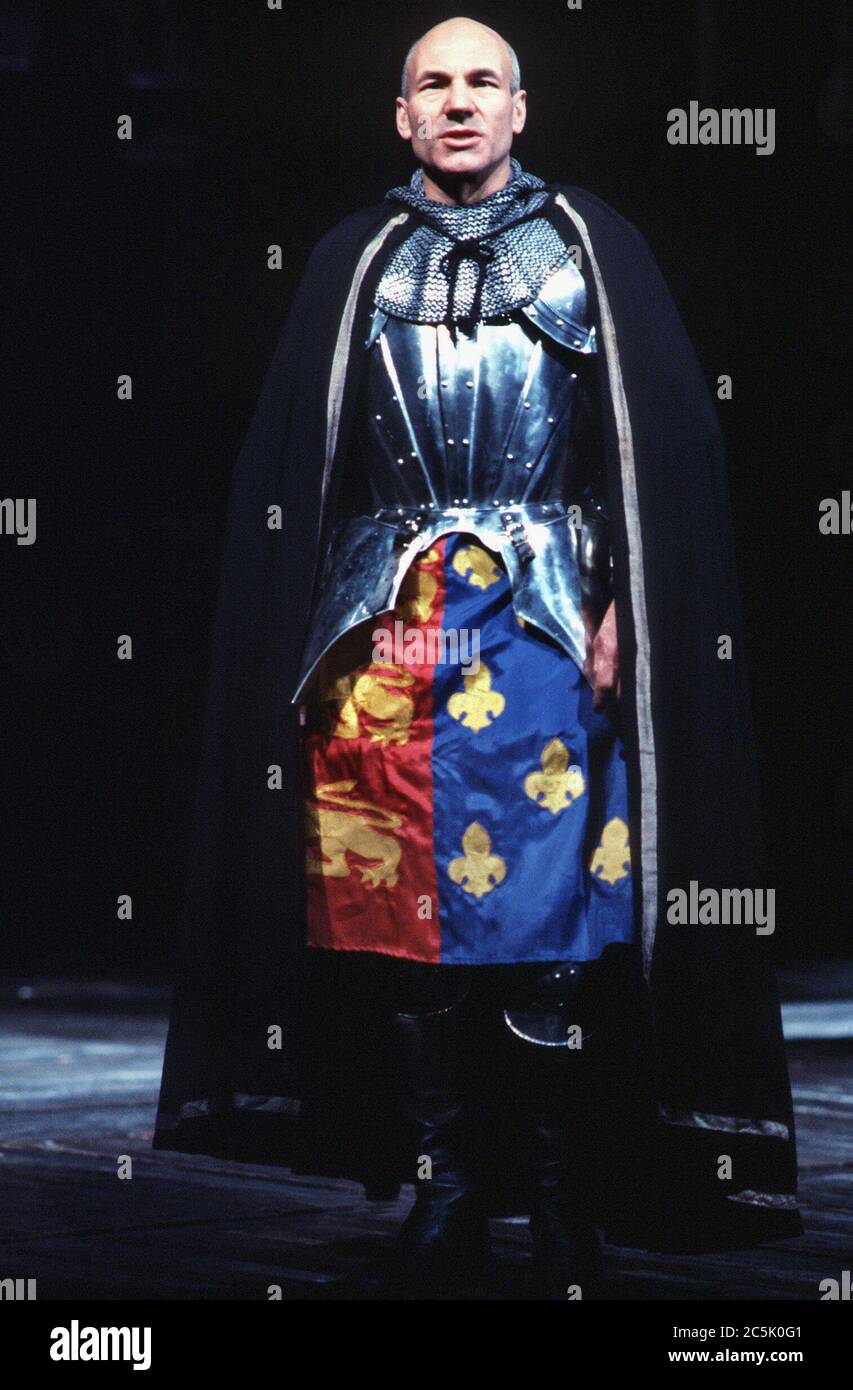

Philip Voss as a wily Worcester and a gullible Shallow, Robert East as a treacherous Northumberland and a sozzled Silence, and Michael Mears as a red-faced Bardolph and an empurpled Archbishop are the symbols of an astonishingly versatile company. Ben Mansfield also lends Hotspur, whom Henry foolishly wishes had been his own offspring, with exactly the right blend of chivalric glamour and macho intemperance.īut this is a cast that bats all the way down. David Yelland endows Hal's true father, the king, with a richly neurotic mix of historic guilt, paternal anguish and insomniac restlessness. Hall constantly reminds us this is a private drama of fathers and sons played out against a political backdrop of civil disorder. And when Mison assumes power as Henry V, he implies that the dismissal of Falstaff exacts its own personal cost. You feel Mison is constantly trying to tell Falstaff that things can't last yet, on the battlefield at Shrewsbury, he tenderly kisses the supposedly dead knight. "Banish plump Jack and banish all the world," cries Falstaff, to which Mison replies, "I do" in the voice of his father and then "I will" in his own steely register. In the great, role-playing tavern scene where Hal assumes his father's identity, Mison gives due warning of his intentions. There is something chilling about his dismissal of his ragged, wartime recruits as "food for powder" and about his ruthless exploitation of his old collegiate chum, Justice Shallow. In his blend of seductiveness and selfishness, Barrit is the best Falstaff since Robert Stephens.īut the complexity of the Hal-Falstaff relationship is enhanced by Tom Mison's admirable Prince.

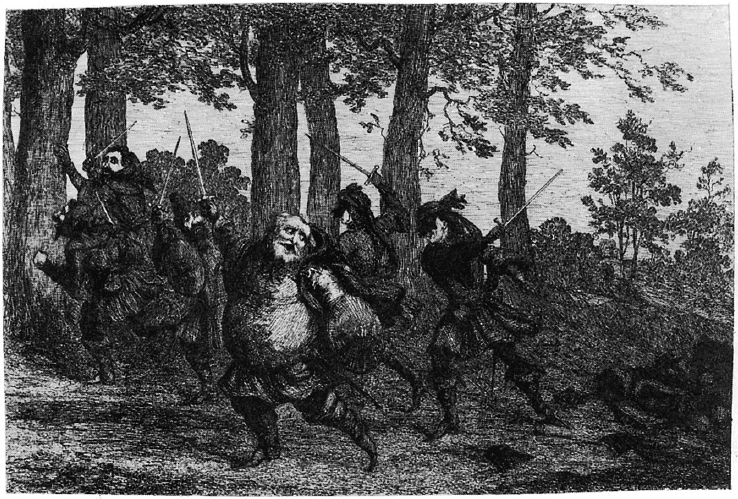

Barrit never sentimentalises Falstaff's calculating cruelty, however. That is due, in no small part, to the multifaceted nature of Desmond Barrit's magnificent Falstaff.īarrit gives us all of the character's easy, companionable charm: taxed by the Prince over his flight from the Gadshill robbery, you can see Barrit racking his brains to come up with an explanation. Yet the production retains its epic sweep thanks to Simon Higlett's superb set, in which a brick wall opens up to provide a panorama of English life.Īt the heart of the plays lies the quest for good government, which inevitably involves Prince Hal's rejection of Falstaff and it is a sign of the production's success that we understand both the human cost and political necessity of the decision. And when Lizzie McInnerny's Mistress Quickly complains to Falstaff that "thou didst swear to me upon a parcel-gilt goblet, sitting in my dolphin chamber, at the round table, by a sea-coal fire, upon Wednesday in Whitsun-week", she anticipates the garrulous particularity of Pickwick's Mrs Bardell. Sir John Falstaff's lowlife cronies have the spiky angularity of a Phiz illustration to a Dickens novel. Hall has taken an initially surprising decision: to dress the plays in early Victorian costume. Yet within the overall pattern, his productions are filled with a mass of complex human detail. He never lets us forget that they are about the search for order in a divided, burning land. Peter Hall, returning to them for the first time since he directed them at Stratford in 1964, has also realised them to perfection. I t is now widely accepted that these two plays represent the twin summits of William Shakespeare's genius.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)